What Art Style Is Depicted in the Kama Sutra

Two folios from a palm leaf manuscript of the Kamasutra text (Sanskrit, Devanagari script). | |

| Author | Vatsyayana Mallanaga |

|---|---|

| Original title | कामसूत्र |

| Translator | Many |

| Country | Classical Age, Bharat |

| Language | Sanskrit |

| Subject | The art of living well, the nature of love, finding a life partner, maintaining one's love life, and other aspects pertaining to pleasure-oriented faculties of human life |

| Genre | Sutra Literature |

| Set up in | 2nd - 3rd CE |

| Published in English | 1883 |

The Kama Sutra (; Sanskrit: कामसूत्र, ![]() pronunciation(help·info) , Kāma-sūtra ; lit. 'Principles of Love') is an aboriginal Indian[1] [2] Sanskrit text on sexuality, eroticism and emotional fulfillment in life.[three] [4] [v] Attributed to Vātsyāyana,[six] The Kama Sutra is neither exclusively nor predominantly a sex transmission on sexual activity positions,[3] just rather was written every bit a guide to the art of living well, the nature of beloved, finding a life partner, maintaining ane's love life, and other aspects pertaining to pleasance-oriented faculties of human life.[iii] [7] [8] It is a sutra-genre text with terse aphoristic verses that take survived into the modernistic era with different bhāṣyas (exposition and commentaries). The text is a mix of prose and anustubh-meter poetry verses. The text acknowledges the Hindu concept of Purusharthas, and lists desire, sexuality, and emotional fulfillment every bit one of the proper goals of life. Its chapters discuss methods for courtship, training in the arts to be socially engaging, finding a partner, flirting, maintaining power in a married life, when and how to commit adultery, sexual positions, and other topics.[9] The bulk of the book is virtually the philosophy and theory of love, what triggers desire, what sustains it, and how and when it is practiced or bad.[10] [11]

pronunciation(help·info) , Kāma-sūtra ; lit. 'Principles of Love') is an aboriginal Indian[1] [2] Sanskrit text on sexuality, eroticism and emotional fulfillment in life.[three] [4] [v] Attributed to Vātsyāyana,[six] The Kama Sutra is neither exclusively nor predominantly a sex transmission on sexual activity positions,[3] just rather was written every bit a guide to the art of living well, the nature of beloved, finding a life partner, maintaining ane's love life, and other aspects pertaining to pleasance-oriented faculties of human life.[iii] [7] [8] It is a sutra-genre text with terse aphoristic verses that take survived into the modernistic era with different bhāṣyas (exposition and commentaries). The text is a mix of prose and anustubh-meter poetry verses. The text acknowledges the Hindu concept of Purusharthas, and lists desire, sexuality, and emotional fulfillment every bit one of the proper goals of life. Its chapters discuss methods for courtship, training in the arts to be socially engaging, finding a partner, flirting, maintaining power in a married life, when and how to commit adultery, sexual positions, and other topics.[9] The bulk of the book is virtually the philosophy and theory of love, what triggers desire, what sustains it, and how and when it is practiced or bad.[10] [11]

The text is i of many Indian texts on Kama Shastra.[12] Information technology is a much-translated piece of work in Indian and non-Indian languages. The Kamasutra has influenced many secondary texts that followed afterwards the 4th-century CE, as well as the Indian arts every bit exemplified by the pervasive presence Kama-related reliefs and sculpture in former Hindu temples. Of these, the Khajuraho in Madhya Pradesh is a UNESCO Globe Heritage Site.[13] Among the surviving temples in north India, one in Rajasthan sculpts all the major chapters and sexual positions to illustrate the Kamasutra.[14] Co-ordinate to Wendy Doniger, the Kamasutra became "one of the most pirated books in English language" soon afterwards it was published in 1883 past Richard Burton. This first European edition by Burton does not faithfully reflect much in the Kamasutra because he revised the collaborative translation by Bhagavanlal Indrajit and Shivaram Parashuram Bhide with Forster Arbuthnot to suit 19th-century Victorian tastes.[fifteen]

A Kamasutra manuscript folio preserved in the vaults of the Raghunath Temple in Jammu & Kashmir.

The original composition date or century for the Kamasutra is unknown. Historians have variously placed it between 400 BCE and 300 CE.[16] According to John Keay, the Kama Sutra is a compendium that was collected into its nowadays form in the second century CE.[17] In contrast, the Indologist Wendy Doniger, who has co-translated the Kama Sutra and published many papers on related Hindu texts, the surviving version of the Kama Sutra must accept been revised or composed after 225 CE considering it mentions the Abhiras and the Andhras dynasties that did not co-dominion major regions of ancient Republic of india before that year.[18] The text makes no mention of the Gupta Empire which ruled over major urban areas of ancient Bharat, reshaping aboriginal Indian arts, Hindu civilization and economy from the quaternary century through the 6th century. For these reasons, she dates the Kama Sutra to the second half of the tertiary century CE.[xviii]

The place of its composition is besides unclear. The likely candidates are urban centers of north India, alternatively in the eastern urban Pataliputra (now Patna).[xix] Doniger notes Kama Sutra was composed "sometime in the tertiary century of the mutual era, most likely in its second half, at the dawn of the Gupta Empire".[20]

Vatsyayana Mallanaga is its widely accustomed writer because his proper name is embedded in the colophon verse, merely fiddling is known almost him.[21] Vatsyayana states that he wrote the text after much meditation.[22] In the preface, Vatsyayana acknowledges that he is distilling many aboriginal texts, but these have not survived.[22] He cites the work of others he calls "teachers" and "scholars", and the longer texts by Auddalaki, Babhravya, Dattaka, Suvarnanabha, Ghotakamukha, Gonardiya, Gonikaputra, Charayana, and Kuchumara.[22] Vatsyayana's Kamasutra is mentioned and some verses quoted in the Brihatsamhita of Varahamihira, as well as the poems of Kalidasa. This suggests he lived before the fifth-century CE.[23] [24]

Background

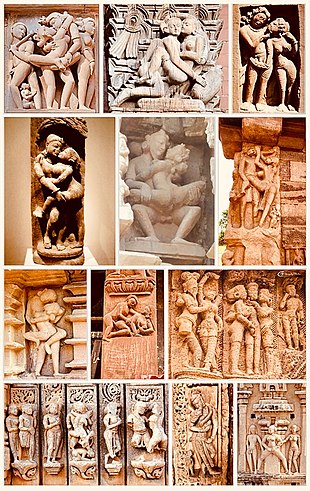

Kama-related arts are common in Hindu temples. These scenes include courtship, amorous couples in scenes of intimacy (mithuna), or a sexual position. Above: 6th- to 14th-century temples in Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Karnataka, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Nepal.

The Hindu tradition has the concept of the Purusharthas which outlines "iv main goals of life".[25] [26] It holds that every man has four proper goals that are necessary and sufficient for a fulfilling and happy life:[27]

- Dharma – signifies behaviors that are considered to be in accord with rta, the gild that makes life and universe possible,[28] and includes duties, rights, laws, conduct, virtues and right way of living.[29] Hindu dharma includes the religious duties, moral rights and duties of each individual, equally well every bit behaviors that enable social order, right conduct, and those that are virtuous.[29] Dharma, according to Van Buitenen,[30] is that which all existing beings must accept and respect to sustain harmony and order in the globe. Information technology is, states Van Buitenen, the pursuit and execution of one'south nature and true calling, thus playing 1's role in catholic concert.[30]

- Artha – signifies the "means of life", activities and resources that enables 1 to be in a state one wants to exist in.[31] Artha incorporates wealth, career, activity to make a living, financial security and economic prosperity. The proper pursuit of artha is considered an important aim of human life in Hinduism.[32] [33]

- Kama – signifies desire, wish, passion, emotions, pleasure of the senses, the aesthetic enjoyment of life, affection, or dearest, with or without sexual connotations.[34] Gavin Overflowing explains[35] kāma as "honey" without violating dharma (moral responsibleness), artha (material prosperity) and one's journey towards moksha (spiritual liberation).

- Moksha – signifies emancipation, liberation or release.[36] In some schools of Hinduism, moksha connotes freedom from saṃsāra, the wheel of expiry and rebirth, in other schools moksha connotes freedom, self-knowledge, self-realization and liberation in this life.[37] [38]

Each of these pursuits became a subject of study and led to prolific Sanskrit and some Prakrit languages literature in ancient India. Along with Dharmasastras, Arthasastras and Mokshasastras, the Kamasastras genre have been preserved in palm leaf manuscripts. The Kamasutra belongs to the Kamasastra genre of texts. Other examples of Hindu Sanskrit texts on sexuality and emotions include the Ratirahasya (called Kokashastra in some Indian scripts), the Anangaranga, the Nagarasarvasva, the Kandarpachudmani, and the Panchasayaka.[39] [40] [41] The defining object of the Indian Kamasastra literature, according to Laura Desmond – an anthropologist and a professor of Religious Studies, is the "harmonious sensory experience" from a good human relationship between "the self and the globe", by discovering and enhancing sensory capabilities to "affect and be afflicted by the earth".[41] Vatsyayana predominantly discusses Kama along with its human relationship with Dharma and Artha. He makes a passing mention of the 4th aim of life in some verses.[42]

Vedic heritage

The earliest foundations of the kamasutra are found in the Vedic era literature of Hinduism.[43] [44] Vatsyayana acknowledges this heritage in poetry one.ane.ix of the text where he names Svetaketu Uddalaka as the "get-go human author of the kamasutra". Uddalaka is an early Upanishadic rishi (scholar-poet, sage), whose ideas are found in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad such as in section 6.two, and the Chandogya Upanishad such as over the verses five.iii through 5.10.[43] These Hindu scriptures are variously dated betwixt 900 BCE and 700 BCE, according to the Indologist and Sanskrit scholar Patrick Olivelle. Among with other ideas such as Atman (self, soul) and the ontological concept of Brahman, these early Upanishads discuss human being life, activities and the nature of existence equally a form of internalized worship, where sexuality and sex is mapped into a class of religious yajna ritual (sacrificial fire, Agni) and suffused in spiritual terms:[43]

A burn down – that is what a woman is, Gautama.

Her firewood is the vulva,

her smoke is the pubic hair,

her flame is the vagina,

when one penetrates her, that is her embers,

and her sparks are the climax.

In that very fire the gods offer semen,

and from that offering springs a man.– Brihadaranyaka Upanishad half dozen.2.thirteen, c. 700 BCE, Trans.: Patrick Olivelle[45] [46]

According to the Indologist De, a view with which Doniger agrees, this is one of the many evidences that the kamasutra began in the religious literature of the Vedic era, ideas that were ultimately refined and distilled into a sutra-genre text by Vatsyayana.[44] Co-ordinate to Doniger, this paradigm of celebrating pleasures, enjoyment and sexuality as a dharmic human action began in the "earthy, vibrant text known equally the Rigveda" of the Hindus.[47] The Kamasutra and celebration of sex, eroticism and pleasure is an integral function of the religious milieu in Hinduism and quite prevalent in its temples.[48] [49]

Epics

Homo relationships, sexual practice and emotional fulfillment are a significant office of the post-Vedic Sanskrit literature such as the major Hindu epics: the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. The ancient Indian view has been, states Johann Meyer, that love and sex are a delightful necessity. Though she is reserved and selective, "a woman stands in very not bad need of surata (amorous or sexual pleasure)", and "the woman has a far stronger erotic disposition, her delight in the sexual act is greater than a man'south".[fifty]

Manuscripts

The Kamasutra manuscripts have survived in many versions across the Indian subcontinent. While attempting to go a translation of the Sanskrit kama-sastra text Anangaranga that had already been widely translated by the Hindus in regional languages such as Marathi, assembly of the British Orientalist Richard Burton stumbled into portions of the Kamasutra manuscript. They commissioned the Sanskrit scholar Bhagvanlal Indraji to locate a consummate Kamasutra manuscript and translate it. Indraji nerveless variant manuscripts in libraries and temples of Varanasi, Kolkata and Jaipur. Burton published an edited English translation of these manuscripts, but not a disquisitional edition of the Kamasutra in Sanskrit.[51]

According to S.C. Upadhyaya, known for his 1961 scholarly study and a more than accurate translation of the Kamasutra, in that location are issues with the manuscripts that accept survived and the text probable underwent revisions over time.[52] This is confirmed by other 1st-millennium CE Hindu texts on kama that mention and cite the Kamasutra, merely some of these quotations credited to the Kamasutra past these celebrated authors "are not to be plant in the text of the Kamasutra" that take survived.[52] [53]

Contents

Vatsyayana's Kama Sutra states it has 1,250 verses distributed over 36 chapters in 64 sections organised into 7 books.[54] This statement is included in the opening chapter of the text, a common exercise in ancient Hindu texts probable included to forestall major and unauthorized expansions of a pop text.[55] The text that has survived into the modern era has 67 sections, and this list is enumerated in Book 7 and in Yashodhara'southward Sanskrit commentary (bhasya) on the text.[55]

The Kamasutra uses a mixture of prose and verse, and the narration has the grade of a dramatic fiction where ii characters are called the nayaka (man) and nayika (woman), aided by the characters chosen pitamarda (libertine), vita (pander) and vidushaka (jester). This format follows the teachings found in the Sanskrit classic named the Natyasastra.[56] The teachings and discussions institute in the Kamasutra extensively incorporate ancient Hindu mythology and legends.[57]

| Book.Affiliate | Verses | Topics[58] [59] [threescore] |

| 1 | General remarks | |

| one.one | i–24 | Preface, history of kama literature, outline of the contents |

| ane.2 | i–40 | Suitable age for kama noesis, the three goals of life: dharma, Artha, Kama; their essential interrelationship, natural human being questions |

| i.iii | 1–22 | Preparations for kama, threescore four arts for a better quality of life, how girls tin learn and railroad train in these arts, their lifelong benefits and contribution to ameliorate kama |

| 1.iv | one–39 | The life of an urban gentleman, work routine, entertainment and festivals, sports, picnics, socialization, games, entertainment and drinking parties, finding aids (messengers, friends, helpers) to improve success in kama, options for rural gentlemen, what i must never practice in their pursuit of kama |

| 1.five | ane–37 | Types of women, finding sexual partners, sex, being lovers, being faithful, permissible women, infidelity and when to commit it, the forbidden women whom 1 must avoid, discretion with messengers and helpers, few dos and don't in life |

| ii | Amorous advances/sexual union | |

| 2.1 | i–45 | Sexual relationships and the pleasure of sex, uniqueness of every lover, temperaments, sizes, endurance, foreplay, types of love and lovers, duration of sex, types of climax, intimacy, joy |

| 2.2 | i–31 | Figuring out if someone is interested, conversations, prelude and preparation, touching each other, massage, embracing |

| 2.3–5 | ane–32, i–31, 1–43 | Kissing, where to kiss and how, teasing each other and games, signals and hints for the other person, cleanliness, taking care of teeth, hair, body, nails, concrete not-sexual forms of intimacy (scratching, poking, biting, slapping, belongings her) |

| 2.vi–10 | 1–52 | Intercourse, what it is and how, positions, various methods, bringing multifariousness, usual and unusual sexual practice, communicating earlier and during intercourse (moaning), diverse regional practices and community, the needs of a man, the needs of a woman, variations and surprises, oral sex for women, oral sexual activity for men, opinions, disagreements, experimenting with each other, the showtime fourth dimension, why sexual excitement fades, reviving passion, quarreling, keeping sex exciting, lx four methods to find happiness in a committed relationship |

| 3 | Acquiring a wife | |

| 3.1 | ane–24 | Wedlock, finding the right girl, which i to avoid, which 1 to persuade, how to decide, how to proceed, making alliances |

| iii.2–three | ane–35, ane–32 | Earning her trust, importance of not rushing things and beingness gentle, moving towards sexual openness gradually, how to approach a adult female, proceeding to friendship, from friendship to intimacy, interpreting different responses of a girl |

| three.four–5 | 1–55, 1–30 | Earning his trust, knowing the man and his advances, how a woman can make advances, winning the heart; utilizing confidants of your lover, types of union, formalizing union, eloping |

| 4 | Duties and privileges of the married woman | |

| 4.1–2 | one–48, i–30 | Being a wife, her life, bear, power over the household, duties when her married man is away, nuclear and joint families, when to take charge and when not to |

| iv.2 | xxx–72 | Remarriage, being unlucky, harems,[note one] polygamy |

| v | Other men's wives | |

| 5.1 | i–56 | Homo nature, tendencies of men, tendencies of women, why women lose interest and showtime looking elsewhere, avoiding adultery, pursuing adultery, finding women interested in extramarital sexual activity |

| 5.2–5 | 1–28, one–28, 1–66, 1–37 | Finding many lovers, deploying messengers, the need for them and how to find good go-betweens, getting acquainted, how to make a pass, gifts and dearest tokens, arranging meetings, how to discretely find out if a woman is available and interested, warnings and knowing when to stop |

| v.vi | 1–48 | Public women [prostitution], their life, what to expect and not, how to find them, regional practices, guarding and respecting them |

| 6 | Near courtesans | |

| 6.1 | 1–33 | Courtesans, what motivates them, how to find clients, deciding if someone should merely be a friend or a lover, which lovers to avoid, getting a lover and keeping him interested |

| 6.2 | 1–76 | How to please your lover |

| six.3 | 1–46 | Making a lover become crazy about you, how to go rid of him if dear life is not fulfilling |

| 6.iv–5 | one–43, 1–39 | Methods to brand an ex-lover interested in you lot again, reuniting, methods, checking if it is worth the effort, types of lovers, things to consider |

| half dozen.6 | 1–53 | Why love life gets dull, examples, familiarity and doubts |

| 7 | Occult practices | |

| 7.1–two | 1–51, one–51 | Looking skilful, feeling good, why and how to be attractive, bewitching, existence virile, paying attention, genuineness and artificiality, torso art and perforations, taking care of ane's sexual organs, stimulants, prescriptions and unusual practices |

Discussion

On balance in life

In any menstruum of life in which

ane of the elements of the trivarga

– dharma, artha, kama –

is the principal one, the other 2

should be natural adjuncts of it.

Under no circumstances, should whatsoever i of the

trivarga be detrimental to the other two.

—Kamasutra 1.two.1,

Translator: Ludo Rocher[62]

Across human cultures, states Michel Foucault, "the truth of sex" has been produced and shared by two processes. One method has been ars erotica texts, while the other has been the scientia sexualis literature. The first are typically of the hidden variety and shared past 1 person to some other, betwixt friends or from a master to a pupil, focusing on the emotions and feel, sans physiology. These bury many of the truths almost sex and human sexual nature.[63] [64] The 2nd are empirical studies of the blazon plant in biology, physiology and medical texts, focusing on the physiology and objective observations, sans emotions.[63] [64] The Kamasutra belongs to both camps, states Doniger. It discusses, in its distilled form, the physiology, the emotions and the experience while citing and quoting prior Sanskrit scholarship on the nature of kama.[64]

The Kamasutra is a "sutra"-genre text consisting of intensely condensed, aphoristic verses. Doniger describes them as a "kind of atomic string (thread) of meanings", which are so ambiguous that whatsoever translation is more similar deciphering and filling in the text.[64] Condensing a text into a sutra-genre religious text form makes it easier to call up and transmit, but it also introduces ambiguity and the need to sympathize the context of each chapter, its philological roots, as well as the prior literature, states Doniger.[64] However, this method of knowledge preservation and transmission has its foundation in the Vedas, which themselves are cryptic and crave a commentator and teacher-guide to encompass the details and the inter-relationship of the ideas.[64] [65] The Kamasutra likewise has attracted commentaries, of which the about well known are those of twelfth-century[65] or 13th-century[66] Yaśodhara's Jayamaṅgalā in the Sanskrit language, and of Devadatta Shastri who commented on the original text as well as its commentaries in the Hindi language.[64] [67] In that location are many other Sanskrit commentaries on the Kamasutra, such equally the Sutra Vritti by Narsingha Sastri.[65] These commentaries on the Kamasutra cite and quote text from other Hindu texts such every bit the Upanishads, the Arthashastra, the Natyashastra, the Manusmriti, the Nyayasutra, the Markandeya Purana, the Mahabharata, the Nitishastra and others to provide the context, per the norms of its literary traditions.[68] The extant translations of the Kamasutra typically contain these commentaries, states Daniélou.[69]

In the colonial era marked by sexual censorship, the Kamasutra became famous as a pirated and hole-and-corner text for its explicit clarification of sex positions. The stereotypical image of the text is one where erotic pursuit with sexual intercourse include improbable contortionist forms.[70] In reality, co-ordinate to Doniger, the existent Kamasutra is much more and is a volume well-nigh "the fine art of living", about understanding one's torso and a partner's body, finding a partner and emotional connectedness, wedlock, the ability equation over time in intimate relationships, the nature of adultery and drugs (aphrodisiacs[71]) along with many uncomplicated to complex variations in sex positions to explore. It is also a psychological treatise that presents the event of desire and pleasance on human behavior.[70]

For each attribute of Kama, the Kamasutra presents a diverse spectrum of options and regional practices. According to Shastri, as quoted by Doniger, the text analyses "the inclinations of men, good and bad", thereafter it presents Vatsyayana's recommendation and arguments of what one must avoid besides every bit what to non miss in experiencing and enjoying, with "acting only on the proficient".[72] For example, the text discusses adultery but recommends a faithful spousal relationship.[72] [73] The approach of Kamasutra is not to ignore nor deny the psychology and complication of human behavior for pleasure and sex. The text, according to Doniger, conspicuously states "that a treatise demands the inclusion of everything, good or bad", just afterwards being informed with in-depth knowledge, 1 must "reverberate and accept just the good". The approach found in the text is one where goals of scientific discipline and faith should not be to repress, but to encyclopedically know and understand, thereafter let the individual make the choice.[72] The text states that information technology aims to be comprehensive and inclusive of diverse views and lifestyles.[74]

Flirting and courtship

The 3rd-century text includes a number of themes, including subjects such equally flirting that resonate in the modernistic era context, states a New York Times review.[75] For case, information technology suggests that a boyfriend seeking to attract a adult female, should hold a political party, and invite the guests to recite poesy. In the party, a poem should be read with parts missing, and the guests should compete to creatively complete the poem.[75] Every bit another instance, the Kamasutra suggests that the male child and the daughter should go play together, such equally swim in a river. The boy should swoop into the water abroad from the daughter he is interested in, then swim underwater to go close to her, emerge from the h2o and surprise her, touch her slightly and then dive again, away from her.[75]

Book 3 of the Kamasutra is largely defended to the art of courtship with the aim of marriage. The book's opening verse declares marriage to be a conducive means to "a pure and natural love between the partners", states Upadhyaya.[76] It leads to emotional fulfillment in many forms such as more friends for both, relatives, progeny, dotty and sexual human relationship between the couple, and the bridal pursuit of dharma (spiritual and ethical life) and artha (economic life).[76] The first three chapters talk over how a man should become about finding the right helpmate, while the fourth offers equivalent word for a adult female and how she can become the man she wants.[76] The text states that a person should be realistic, and must possess the "same qualities which one expects from the partner". It suggests involving one's friends and relatives in the search, and meeting the current friends and relatives of one'due south future partner prior to the marriage.[76] While the original text makes no mention of astrology and horoscopes, later commentaries on the Kamasutra such every bit one by 13th-century Yashodhara includes consulting and comparing the compatibility of the horoscopes, omens, planetary alignments, and such signs prior to proposing a marriage. Vatsyayana recommends, states Alain Danielou, that "ane should play, marry, associate with one's equals, people of one'southward own circle" who share the same values and religious outlook. It is more than difficult to manage a good, happy relationship when in that location are basic differences between the ii, according to verse 3.1.20 of the Kamasutra.[77]

Intimacy and foreplay

Vatsyayana'southward Kamasutra describes intimacy of various forms, including those between lovers before and during sexual practice. For example, the text discusses eight forms of alingana (embrace) in verses 2.2.vii–23: sphrishtaka, viddhaka, udghrishtaka, piditaka, lataveshtitaka, vrikshadhirudha, tilatandula and kshiranira.[78] The start 4 are expressive of mutual love, but are nonsexual. The concluding four are forms of embrace recommended by Vatsyayana to increase pleasure during foreplay and during sexual intimacy. Vatsyayana cites earlier – now lost – Indian texts from the Babhraya's school, for these eight categories of embraces. The various forms of intimacy reverberate the intent and provide means to appoint a combination of senses for pleasure. For example, according to Vatsyayana the lalatika form enables both to experience each other and allows the human to visually capeesh "the full beauty of the female person form", states S.C. Upadhyaya.[78]

On sexual embraces

Some sexual embraces, not in this text,

as well intensify passion;

these, too, may be used for love-making,

merely but with intendance.

The territory of the text extends

only then far equally men accept dull appetites;

but when the wheel of sexual ecstasy is in full motion,

there is no textbook at all, and no order.

—Kamasutra two.2.30–31,

Translator: Wendy Doniger and Sudhir Kakar[79]

Another instance of the forms of intimacy discussed in the Kamasutra includes chumbanas (kissing).[fourscore] The text presents twenty-six forms of kisses, ranging from those appropriate for showing respect and amore, to those during foreplay and sex. Vatsyayana also mentions variations in kissing cultures in unlike parts of ancient India.[80] The best kiss for an intimate partner, according to kamasutra, is one that is based on the sensation of the avastha (the emotional state of 1'south partner) when the two are non in a sexual marriage. During sexual activity, the text recommends going with the flow and mirroring with abhiyoga and samprayoga.[fourscore]

Other techniques of foreplay and sexual intimacy described in the kamasutra include various forms of holding and embraces (grahana, upaguhana), common massage and rubbing (mardana), pinching and biting, using fingers and easily to stimulate (karikarakrida, nadi-kshobana, anguli-pravesha), three styles of jihva-pravesha (french kissing), and many styles of fellatio and cunnlingus.[81]

Adultery

The Kamasutra, states the Indologist and Sanskrit literature scholar Ludo Rocher, discourages adultery only then devotes "not less than fifteen sutras (ane.v.6–twenty) to enumerating the reasons (karana) for which a man is allowed to seduce a married woman". Vatsyayana mentions different types of nayikas (urban girls) such equally unmarried virgins, those married and abandoned past husband, widow seeking remarriage and courtesans, then discusses their kama/sexual education, rights and mores.[82] In babyhood, Vātsyāyana says, a person should learn how to make a living; youth is the time for pleasure, and as years pass, one should concentrate on living virtuously and hope to escape the bicycle of rebirth.[ citation needed ]

According to Doniger, the Kamasutra teaches adulterous sexual liaison as a means for a man to predispose the involved woman in profitable him, as a strategic ways to work against his enemies and to facilitate his successes. It as well explains the signs and reasons a woman wants to enter into an adulterous human relationship and when she does not want to commit infidelity.[83] The Kamasutra teaches strategies to appoint in adulterous relationships, simply concludes its affiliate on sexual liaison stating that one should non commit adultery because infidelity pleases simply 1 of two sides in a marriage, hurts the other, it goes against both dharma and artha.[73]

Caste, grade

The Kamasutra has been one of the unique sources of sociological data and cultural milieu of aboriginal India. It shows a "near total condone of class (varna) and caste (jati)", states Doniger.[84] Human relationships, including the sexual type, are neither segregated nor repressed by gender or caste, rather linked to individual's wealth (success in artha). In the pages of the Kamasutra, lovers are "not upper-class" but they "must exist rich" enough to dress well, pursue social leisure activities, buy gifts and surprise the lover. In the rare mention of caste found in the text, it is most a man finding his legal wife and the communication that humorous stories to seduce a adult female should be virtually "other virgins of same jati (caste)". In full general, the text describes sexual practice between men and women across grade and caste, both in urban and rural settings.[84]

Same-sex relationships

The Kamasutra includes verses describing homosexual relations such every bit oral sex betwixt 2 men, too as between two women.[85] [86] Lesbian relations are extensively covered in Chapters 5 and eight in Volume two of the text.[87]

According to Doniger, the Kamasutra discusses aforementioned-sex relationships through the notion of the tritiya prakriti, literally, "third sexuality" or "third nature". In Redeeming the Kamasutra, Doniger states that "the Kamasutra departs from the dharmic view of homosexuality in meaning ways", where the term kliba appears. In contemporary translations, this has been inaccurately rendered as "eunuch" – or, a castrated man in a harem,[note one] and the royal harem did not be in Republic of india earlier the Turkish presence in the 9th century.[88] The Sanskrit word Kliba establish in older Indian texts refers to a "human who does not act similar a man", typically in a pejorative sense. The Kamasutra does not use the pejorative term kliba at all, but speaks instead of a "tertiary nature" or, in the sexual behavior context as the "third sexuality".[88]

The text states that there are two sorts of "third nature", one where a man behaves similar a adult female, and in the other, a woman behaves like a human being. In 1 of the longest consecutive sets of verses describing a sexual human activity, the Kamasutra describes fellatio technique between a man dressed like a woman performing fellatio on another human.[88] The text as well mentions same-sex behavior between two women, such as a girl losing her virginity with a girlfriend as they use their fingers,[89] likewise as oral sex and the use of sex toys between women.[ninety] Svairini, a term Danielou translates as a lesbian,[91] is described in the text as a woman who lives a conjugal life with another woman or by herself fending for herself, not interested in a husband.[92] Additionally, the text has some fleeting remarks on bisexual relationships.[89]

The Kamasutra also mentions "pretend play" sadomasochism,[93] [94] and group sex.[95]

Translations

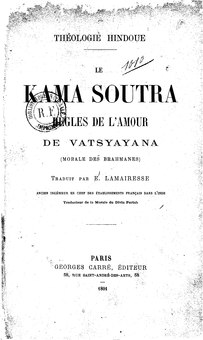

The get-go English version past Richard Burton became public in 1883, only information technology was illegal to publish information technology in England and the United states till 1962.[96] Right: a French retranslation of 1891.

Co-ordinate to Doniger, the historical records suggest that the Kamasutra was a well-known and popular text in Indian history. This popularity through the Mughal Empire era is confirmed by its regional translations. The Mughals, states Doniger, had "commissioned lavishly illustrated Persian and Sanskrit Kamasutra manuscripts".[97]

The starting time English translation of the Kama Sutra was privately printed in 1883 by the Orientalist Sir Richard Francis Burton. He did non translate it, but did edit it to accommodate the Victorian British attitudes. The unedited translation was produced by the Indian scholar Bhagwan Lal Indraji with the assist of a educatee Shivaram Parshuram Bhide, under the guidance of Burton's friend, the Indian civil servant Forster Fitzgerald Arbuthnot.[98] According to Doniger, the Burton version is a "flawed English language translation" merely influential as modern translators and abridged versions of Kamasutra even in the Indian languages such equally Hindi are re-translations of the Burton version, rather than the original Sanskrit manuscript.[96]

The Burton version of the Kamasutra was produced in an surround where Victorian mindset and Protestant proselytizers were busy finding faults and attacking Hinduism and its culture, rejecting every bit "filthy paganism" anything sensuous and sexual in Hindu arts and literature. The "Hindus were cowering nether their scorn", states Doniger, and the open give-and-take of sex in the Kamasutra scandalized the 19th-century Europeans.[96] The Burton edition of the Kamasutra was illegal to publish in England and the U.s. till 1962. Yet, states Doniger, it became soon after its publication in 1883, "i of the most pirated books in the English language", widely copied, reprinted and republished sometimes without Richard Burton's proper noun.[96]

Burton made 2 important contributions to the Kamasutra. Starting time, he had the courage to publish information technology in the colonial era against the political and cultural mores of the British elite. He creatively found a manner to subvert the then prevalent censorship laws of Great britain nether the Obscene Publications Deed of 1857.[99] [96] Burton created a fake publishing house named The Kama Shastra Gild of London and Benares (Benares = Varanasi), with the announcement that it is "for private circulation just".[96] The second major contribution was to edit it in a major fashion, by changing words and rewriting sections to brand it more than adequate to the general British public. For case, the original Sanskrit Kamasutra does not use the words lingam or yoni for sexual organs, and almost always uses other terms. Burton adroitly avoided being viewed every bit obscene to the Victorian mindset by fugitive the utilize of words such equally penis, vulva, vagina and other directly or indirect sexual terms in the Sanskrit text to talk over sex activity, sexual relationships and human sexual positions. Burton used the terms lingam and yoni instead throughout the translation.[100] This conscious and incorrect give-and-take exchange, states Doniger, thus served as an Orientalist means to "anthropologize sex, altitude it, go far safe for English language readers by assuring them, or pretending to assure them, that the text was not nigh real sexual organs, their sexual organs, but merely about the appendages of weird, dark people far away."[100] Though Burton used the terms lingam and yoni for man sexual organs, terms that actually mean a lot more in Sanskrit texts and its pregnant depends on the context. However, Burton'due south Kamasutra gave a unique, specific meaning to these words in the western imagination.[100]

The issues with Burton mistranslation are many, states Doniger. First, the text "only does non say what Burton says information technology says".[96] Second, it "robs women of their voices, turning straight quotes into indirect quotes, thus losing the strength of the dialogue that animates the work and erasing the vivid presence of the many women who speak in the Kamasutra". Third, it changes the forcefulness of words in the original text. For case, when a adult female says "Finish!" or "Permit me go!" in the original text of Vatsyayana, Burton changed it to "She continually utters words expressive of prohibition, sufficiency, or desire of liberation", states Doniger, and thus misconstrues the context and intent of the original text.[96] Similarly, while the original Kamasutra acknowledges that "women have strong privileges", Burton erased these passages and thus eroded women's agency in aboriginal India in the typical Orientialist manner that dehumanized the Indian civilisation.[96] [100] David Shulman, a professor of Indian Studies and Comparative Religion, agrees with Doniger that the Burton translation is misguided and flawed.[75] The Burton version was written with a dissimilar mindset, one that treated "sexual matters with Victorian squeamishness and a pornographic delight in the indirect", according to Shulman. It has led to a misunderstanding of the text and created the wrong impression of it being ancient "Hindu pornography".[75]

In 1961, Due south. C. Upadhyaya published his translation as the Kamasutra of Vatsyayana: Complete Translation from the Original.[101] Co-ordinate to Jyoti Puri, it is considered amidst the best-known scholarly English-linguistic communication translations of the Kamasutra in post-independent India.[102]

Other translations include those by Alain Daniélou (The Complete Kama Sutra in 1994).[103] This translation, originally into French, and thence into English language, featured the original text attributed to Vatsyayana, along with a medieval and a modernistic commentary.[104] Dissimilar the 1883 version, Daniélou'due south new translation preserves the numbered poetry divisions of the original, and does non incorporate notes in the text. He includes English translations of two important commentaries, one past Jayamangala commentary, and a more than modern commentary by Devadatta Shastri, as endnotes.[104] Doniger questions the accurateness of Daniélou'due south translation, stating that he has freely reinterpreted the Kamasutra while disregarding the gender that is implicit in the Sanskrit words. He, at times, reverses the object and subject field, making the woman the discipline and human being the object when the Kamasutra is explicitly stating the opposite. According to Doniger, "fifty-fifty this ambiguous text [Kamasutra] is not infinitely elastic" and such creative reinterpretations do not reflect the text.[105]

A translation by Indra Sinha was published in 1980. In the early on 1990s, its chapter on sexual positions began circulating on the Net every bit an contained text and today is often assumed to be the whole of the Kama Sutra.[106]

Doniger and Sudhir Kakar published another translation in 2002, equally a part of the Oxford Globe's Classics series.[107] Along with the translation, Doniger has published numerous manufactures and book chapters relating to the Kamasutra.[108] [109] [110] The Doniger translation and Kamasutra-related literature has both been praised and criticized. Co-ordinate to David Shulman, the Doniger translation "will change peoples' understanding of this book and of ancient India. Previous translations are hopelessly outdated, inadequate and misguided".[75] Narasingha Sil calls the Doniger's work every bit "another signature work of translation and exegesis of the much misunderstood and abused Hindu erotology". Her translation has the folksy, "twinkle prose", engaging style, and an original translation of the Sanskrit text. However, adds Sil, Doniger's work mixes her postmodern translation and interpretation of the text with her own "political and polemical" views. She makes sweeping generalizations and brassy insertions that are neither supported by the original text nor the weight of evidence in other related ancient and after Indian literature such every bit from the Bengal Renaissance movement – one of the scholarly specialty of Narasingha Sil. Doniger'due south presentation style titillates, notwithstanding some details misinform and parts of her interpretations are dubious, states Sil.[111]

Reception

Indira Kapoor, a director of the International Planned Parenthood Foundation, states that the Kamasutra is a treatise on human being sexual behavior and an ancient endeavor to seriously study sexuality amid other things. According to Kapoor, quotes Jyoti Puri, the attitude of contemporary Indians is markedly different, with misconceptions and expressions of embarrassment, rather than marvel and pride, when faced with texts such equally Kamasutra and amorous and erotic arts found in Hindu temples.[112] Kamasutra, states Kapoor, must be viewed as a ways to discover and improve the "self-conviction and understanding of their bodies and feelings".[112]

The Kamasutra has been a pop reference to erotic ancient literature. In the Western media, such as in the American women's magazine Redbook, the Kamasutra is described as "Although information technology was written centuries ago, there's even so no better sex handbook, which details hundreds of positions, each offering a subtle variation in pleasance to men and women."[113]

Jyoti Puri, who has published a review and feminist critique of the text, states that the "Kamasutra is oft appropriated as indisputable testify of a not-Western and tolerant, indeed celebratory, view of sexuality" and for "the belief that the Kamasutra provides a transparent glimpse into the positive, even exalted, view of sexuality".[114] However, according to Puri, this is a colonial and anticolonial modernist interpretation of the text. These narratives neither resonate with nor provide the "politics of gender, race, nationality and class" in ancient Republic of india published by other historians and that may have been prevalent then.[115]

According to Doniger, the Kama Sutra is a "great cultural masterpiece", one which tin can inspire contemporary Indians to overcome "self-doubts and rejoice" in their ancient heritage.[116]

In popular culture

- Kama Sutra: A Tale of Dearest

- Kamasutra 3D

- Tales of The Kama Sutra: The Perfumed Garden

- Tales of The Kama Sutra 2: Monsoon

Meet also

- History of sexual activity in India

- The Precious stone in The Lotus

- Kamashastra

- Khajuraho Group of Monuments

- Lazzat Un Nisa

- Listing of Indian inventions and discoveries

- Mlecchita vikalpa

- Philaenis

- The Perfumed Garden

- Song of Songs

Explanatory notes

- ^ a b Co-ordinate to Jyoti Puri, the Burton version of Kamasutra "appears to have borrowed material concerning the functioning of the harem in Damascus (Syrian arab republic)" as he edited the text for his colonial era British audience in the tardily 19th-century.[61]

Citations

- ^ Doniger, Wendy (2003). Kamasutra - Oxford World's Classics. Oxford University Press. p. i. ISBN9780192839824.

The Kamasutra is the oldest extant Hindu textbook of erotic beloved. Information technology was composed in Sanskrit, the literary language of aboriginal Bharat, probably in North India and probably sometime in the third century

- ^ Coltrane, Scott (1998). Gender and families. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 36. ISBN9780803990364. Archived from the original on xxx April 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, p. xi.

- ^ Coltrane, Scott (1998). Gender and families. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 36. ISBN978-0-8039-9036-4. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved xv November 2015.

- ^ Wendy Doniger (2003). "The "Kamasutra": It Isn't All about Sex". The Kenyon Review. New Series. 25 (1): 18–37. JSTOR 4338414.

- ^ Haksar & Favre 2011, pp. Introduction, 1–5.

- ^ Carroll, Janell (2009). Sexuality At present: Embracing Diversity. Cengage Learning. p. seven. ISBN978-0-495-60274-3. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved fifteen November 2015.

- ^ Devi, Chandi (2008). From Om to Orgasm: The Tantra Primer for Living in Bliss. AuthorHouse. p. 288. ISBN978-1-4343-4960-six. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, p. xi-xiii.

- ^ Alain Daniélou, The Complete Kama Sutra: The Beginning Unabridged Modern Translation of the Classic Indian Text, ISBN 978-0-89281-525-viii.

- ^ Jacob Levy (2010), Kama sense marketing, iUniverse, ISBN 978-ane-4401-9556-iii, see Introduction

- ^ Flood (1996), p. 65.

- ^ Khajuraho Group of Monuments Archived 16 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine UNESCO Earth Heritage Site

- ^ Ramgarh temple Archived 9 January 2022 at the Wayback Auto, The British Library

- ^ Wendy Doniger (2016). Redeeming the Kamasutra. Oxford University Press. pp. 155–157. ISBN978-0-nineteen-049928-0. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ Sengupta, J. (2006). Refractions of Desire, Feminist Perspectives in the Novels of Toni Morrison, Michèle Roberts, and Anita Desai. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 21. ISBN978-81-269-0629-1. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- ^ John Keay (2010). India: A History: from the Earliest Civilisations to the Boom of the Twenty-first Century. Grove Press. pp. 81–103. ISBN978-0-8021-9550-0. Archived from the original on twenty May 2015. Retrieved ten December 2014.

- ^ a b Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, pp. xi-xii with footnote 2.

- ^ Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, pp. iii-11-xii.

- ^ Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, pp. iii.

- ^ Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, pp. xi–xii.

- ^ a b c Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, p. xii.

- ^ Daniélou 1993, pp. iii–4.

- ^ Varahamihira; 1000 Ramakrishna Bhat (1996). Brhat Samhita of Varahamihira. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 720–721. ISBN978-81-208-1060-0. Archived from the original on 9 January 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ Hopkins, p. 78.

- ^ Flood (1996), p. 17.

- ^ [a] A. Sharma (1982), The Puruṣārthas: a written report in Hindu axiology, Michigan State University, ISBN 978-99936-24-31-8, pp 9–12; Run into review by Frank Whaling in Numen, Vol. 31, 1 (Jul., 1984), pp. 140–142;

[b] A. Sharma (1999), The Puruṣārthas: An Axiological Exploration of Hinduism Archived 29 Dec 2020 at the Wayback Machine, The Periodical of Religious Ideals, Vol. 27, No. ii (Summer, 1999), pp. 223–256;

[c] Chris Bartley (2001), Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy, Editor: Oliver Learman, ISBN 0-415-17281-0, Routledge, Article on Purushartha, pp 443 - ^ The Oxford Dictionary of World Religions, Dharma Archived 26 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Oxford Dictionary of World Religions: "In Hinduism, dharma is a central concept, referring to the order and custom which make life and a universe possible, and thus to the behaviours appropriate to the maintenance of that guild."

- ^ a b Dharma, The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th Ed. (2013), Columbia University Press, Gale, ISBN 978-0-7876-5015-5

- ^ a b J. A. B. Van Buitenen, Dharma and Moksa, Philosophy East and West, Vol. vii, No. 1/2 (April. - Jul., 1957), pp 33–twoscore

- ^ John Koller, Puruṣārtha as Human Aims, Philosophy E and West, Vol. xviii, No. 4 (Oct., 1968), pp. 315–319

- ^ James Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Rosen Publishing, New York, ISBN 0-8239-2287-ane, pp 55–56

- ^ Bruce Sullivan (1997), Historical Dictionary of Hinduism, ISBN 978-0-8108-3327-2, pp 29–30

- ^ Macy, Joanna (1975). "The Dialectics of Desire". Numen. BRILL. 22 (2): 145–60. doi:10.1163/156852775X00095. JSTOR 3269765.

- ^ Gavin Alluvion (1996), The meaning and context of the Purusarthas, in Julius Lipner (Editor) - The Fruits of Our Desiring, ISBN 978-1-896209-30-2, pp 11–13

- ^ John Bowker, The Oxford Lexicon of World Religions, Oxford University Printing, ISBN 978-0-19-213965-8, pp. 650

- ^ See:

- E. Deutsch, The self in Advaita Vedanta, in Roy Perrett (Editor), Indian philosophy: metaphysics, Volume 3, ISBN 0-8153-3608-X, Taylor and Francis, pp 343–360;

- T. Chatterjee (2003), Knowledge and Freedom in Indian Philosophy, ISBN 978-0-7391-0692-ane, pp 89–102; Quote - "Moksa means freedom"; "Moksa is founded on atmajnana, which is the knowledge of the cocky."

- ^ See:

- Jorge Ferrer, Transpersonal knowledge, in Transpersonal Knowing: Exploring the Horizon of Consciousness (editors: Hart et al.), ISBN 978-0-7914-4615-7, State University of New York Press, Chapter x

- Andrew Fort and Patricia Mumme (1996), Living Liberation in Hindu Thought, ISBN 978-0-7914-2706-4;

- ^ Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, pp. xii–13.

- ^ [a] Daud Ali (2011). "Rethinking the History of the "Kāma" World in Early India". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 39 (1): ane–13. doi:10.1007/s10781-010-9115-7. JSTOR 23884104. ;

[b] Daud Ali (2011). "Padmaśrī's "Nāgarasarvasva" and the Globe of Medieval Kāmaśāstra". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 39 (1): 41–62. doi:10.1007/s10781-010-9116-6. JSTOR 23884106. S2CID 170779101. - ^ a b Laura Desmond (2011). "The Pleasure is Mine: The Changing Discipline of Erotic Science". Periodical of Indian Philosophy. Springer. 39 (1): 15–39. doi:ten.1007/s10781-010-9117-5. JSTOR 23884105. S2CID 170502725.

- ^ Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, pp. xi–xvi.

- ^ a b c Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, pp. xiv with footnote 8.

- ^ a b Sushil Kumar De (1969). Ancient Indian Erotics and Erotic Literature. K.50. Mukhopadhyay. pp. 89–92.

- ^ The Early Upanishads. Oxford University Press. 1998. p. 149, context: pp. 143–149. ISBN0-xix-512435-9.

- ^ योषा वा आग्निर् गौतम । तस्या उपस्थ एव समिल् लोमानि धूमो योनिरर्चिर् यदन्तः करोति तेऽङ्गारा अभिनन्दा विस्फुलिङ्गास् तस्मिन्नेतस्मिन्नग्नौ देवा रेतो जुह्वति तस्या आहुत्यै पुरुषः सम्भवति । स जीवति यावज्जीवत्य् अथ यदा म्रियते ।१३, – six.ii.13, For the context and other verses: Wikisource Archived 25 January 2022 at the Wayback Auto

- ^ Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, pp. xiii.

- ^ Y. Krishan (1972). "The Erotic Sculptures of India". Artibus Asiae. 34 (4): 331–343. doi:x.2307/3249625. JSTOR 3249625.

- ^ Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, pp. xi–xvii.

- ^ Johann Jakob Meyer (1989). Sexual Life in Ancient India: A Written report in the Comparative History of Indian Culture. Motilal Banarsidass (Orig: 1953). pp. 229–230, 240–244, context: 229–257 with footnotes. ISBN978-81-208-0638-2. Archived from the original on vii December 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ Jyoti Puri 2002, pp. 614–615.

- ^ a b Vatsyayana; SC Upadhyaya (transl) (1965). Kama sutra of Vatsyayana Complete translation from the original Sanskrit. DB Taraporevala (Orig publication yr: 1961). pp. 52–54. OCLC 150688197.

- ^ Jyoti Puri 2002, pp. 623–624.

- ^ Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, p. xxii.

- ^ a b Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, pp. xxii-xxiii with footnotes.

- ^ Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, p. xxv-xxvi with footnotes.

- ^ Wendy Doniger (2011). "The Mythology of the Kāmasūtra". In H. L. Seneviratne (ed.). The Anthropologist and the Native: Essays for Gananath Obeyesekere. Anthem Press. pp. 293–316. ISBN978-0-85728-435-8. Archived from the original on 9 Jan 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, pp. 3–27 (Volume 1), 28-73 (Book 2), 74–93 (Volume 3), 94–103 (Volume four), 104–129 (Volume v), 131-159 (Volume 6), 161-172 (Book vii).

- ^ Haksar & Favre 2011.

- ^ Vatsyayana; SC Upadhyaya (transl) (1965). Kama sutra of Vatsyayana Complete translation from the original Sanskrit. DB Taraporevala (Orig publication year: 1961). pp. 68–70. OCLC 150688197.

- ^ Puri, Jyoti (2002). "Concerning Kamasutras: Challenging Narratives of History and Sexuality". Signs: Journal of Women in Civilization and Club. Academy of Chicago Press. 27 (iii): 614–616. doi:10.1086/337937. S2CID 143809154. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ Rocher, Ludo (1985). "The Kāmasūtra: Vātsyāyana's Attitude toward Dharma and Dharmaśāstra". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 105 (iii): 521–523. doi:ten.2307/601526. JSTOR 601526.

- ^ a b Michel Foucault (2012). The History of Sexuality: An Introduction. Knopf Doubleday. pp. 57–73. ISBN978-0-307-81928-4. Archived from the original on 9 Jan 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f 1000 Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, pp. fifteen–xvii.

- ^ a b c Daniélou 1993, pp. five–vi.

- ^ Wendy Doniger (2016). Redeeming the Kamasutra. Oxford Academy Press. p. nineteen. ISBN978-0-19-049928-0. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved xx November 2018.

- ^ Albrecht Wezler (2002). Madhav Deshpande; Peter Edwin Claw (eds.). Indian Linguistic Studies: Festschrift in Honor of George Cardona. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 316–322 with footnotes. ISBN978-81-208-1885-9. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 28 Nov 2018.

- ^ Daniélou 1993, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Daniélou 1993, pp. 6–12.

- ^ a b Wendy Doniger (2016). Redeeming the Kamasutra. Oxford University Printing. pp. 20–27. ISBN978-0-19-049928-0. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved twenty November 2018.

- ^ Wendy Doniger (2016). Redeeming the Kamasutra. Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN978-0-19-049928-0. Archived from the original on 21 Dec 2019. Retrieved 20 Nov 2018.

- ^ a b c Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, pp. xx–xxi.

- ^ a b Wendy Doniger (2016). Redeeming the Kamasutra. Oxford University Press. pp. thirteen–fourteen. ISBN978-0-nineteen-049928-0. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, pp. xx–xxii.

- ^ a b c d east f Dinitia Smith (iv May 2002). "A New Kama Sutra Without Victorian Veils". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d Vatsyayana; SC Upadhyaya (transl) (1965). Kama sutra of Vatsyayana Complete translation from the original Sanskrit. DB Taraporevala (Orig publication year: 1961). pp. 69, 141–156. OCLC 150688197.

- ^ Daniélou 1993, pp. 222–224.

- ^ a b Vatsyayana; SC Upadhyaya (transl) (1965). Kama sutra of Vatsyayana Complete translation from the original Sanskrit. DB Taraporevala (Orig publication year: 1961). pp. eleven–12. OCLC 150688197.

- ^ Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, p. xviii.

- ^ a b c Vatsyayana; SC Upadhyaya (transl) (1965). Kama sutra of Vatsyayana Complete translation from the original Sanskrit. DB Taraporevala (Orig publication year: 1961). pp. 12–thirteen. OCLC 150688197.

- ^ Vatsyayana; SC Upadhyaya (transl) (1965). Kama sutra of Vatsyayana Complete translation from the original Sanskrit. DB Taraporevala (Orig publication year: 1961). pp. xi–42. OCLC 150688197.

- ^ Rocher, Ludo (1985). "The Kāmasūtra: Vātsyāyana's Attitude toward Dharma and Dharmaśāstra". Periodical of the American Oriental Gild. 105 (iii): 521–529. doi:10.2307/601526. JSTOR 601526.

- ^ Wendy Doniger (1994). Ariel Glucklich (ed.). The Sense of Adharma. Oxford Academy Press. pp. 170–174. ISBN978-0-19-802448-4. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ a b Wendy Doniger (2016). Redeeming the Kamasutra. Oxford University Press. pp. 21–23. ISBN978-0-19-049928-0. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 20 Nov 2018.

- ^ Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, pp. xxxiv–xxxvii.

- ^ Daniélou 1993, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Daniélou 1993, pp. 169–177.

- ^ a b c Wendy Doniger (2016). Redeeming the Kamasutra. Oxford University Press. pp. 114–116 PDF. ISBN978-0-19-049928-0. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ a b Wendy Doniger (2016). Redeeming the Kamasutra. Oxford Academy Press. pp. 120–122. ISBN978-0-nineteen-049928-0. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved twenty Nov 2018.

- ^ Davesh Soneji (2007). Yudit Kornberg Greenberg (ed.). Encyclopedia of Love in World Religions. ABC-CLIO. p. 307. ISBN978-ane-85109-980-1. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ Daniélou 1993, pp. 48, 171–172.

- ^ P.P. Mishra (2007). Yudit Kornberg Greenberg (ed.). Encyclopedia of Honey in World Religions. ABC-CLIO. p. 362. ISBN978-one-85109-980-ane. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ Vatsyayana; SC Upadhyaya (transl) (1965). Kama sutra of Vatsyayana Complete translation from the original Sanskrit. DB Taraporevala (Orig publication year: 1961). pp. 22–23. OCLC 150688197.

- ^ Wendy Doniger (2016). Redeeming the Kamasutra. Oxford Academy Printing. pp. 39–140. ISBN978-0-19-049928-0. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved twenty November 2018.

- ^ Kumkum Roy (2000). Janaki Nair and Mary John (ed.). A Question of Silence: The Sexual Economies of Modern India. Zed Books. p. 52. ISBN978-1-85649-892-0. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f 1000 h i [a] Sir Richard Burton'southward Version of the Kamasutra Archived 22 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Wendy Doniger, Literary Hub (March xi, 2016);

[b] Wendy Doniger (2018). Against Dharma: Dissent in the Ancient Indian Sciences of Sex and Politics. Yale Academy Press. pp. 164–166. ISBN978-0-300-21619-half-dozen. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2018. - ^ Wendy Doniger (2016). Redeeming the Kamasutra. Oxford Academy Press. p. 12. ISBN978-0-19-049928-0. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved xx November 2018.

- ^ McConnachie (2007), pp. 123–125.

- ^ Ben Grant (2005). "Translating/'The' "Kama Sutra"". Third World Quarterly. Taylor & Francis. 26 (3): 509–510. doi:10.1080/01436590500033867. JSTOR 3993841. S2CID 145438916.

- ^ a b c d Wendy Doniger (2011). "God's Body, or, The Lingam Made Flesh: Conflicts over the Representation of the Sexual Body of the Hindu God Shiva". Social Research. The Johns Hopkins Academy Press. 78 (2): 499–505. JSTOR 23347187.

- ^ Vatsyayana; SC Upadhyaya (transl) (1965). Kama sutra of Vatsyayana Consummate translation from the original Sanskrit. DB Taraporevala (Orig publication twelvemonth: 1961). OCLC 150688197.

- ^ Jyoti Puri 2002, p. 607.

- ^ The Complete Kama Sutra Archived 6 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine by Alain Daniélou.

- ^ a b Daniélou 1993.

- ^ Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002, pp. xxxvi-xxxvii with footnotes.

- ^ Sinha, p. 33.

- ^ Wendy Doniger & Sudhir Kakar 2002.

- ^ Wendy Doniger (2016). Redeeming the Kamasutra. Oxford University Printing. ISBN978-0-19-049928-0. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ Wendy Doniger (2002). "On the Kamasutra". Daedalus. The MIT Press. 131 (2): 126–129. JSTOR 20027767.

- ^ Wendy Doniger (1994). Ariel Glucklich (ed.). The Sense of Adharma. Oxford University Press. pp. 169–174. ISBN978-0-19-802448-four. Archived from the original on 25 Jan 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ Narasingha P. Sil (2018). "Volume Review: Wendy Doniger, Redeeming the Kamasutra". American Journal of Indic Studies. 1 (1): 61–66 with footnotes. doi:ten.12794/journals.ind.vol1iss1pp61-66.

- ^ a b Jyoti Puri 2002, p. 605.

- ^ Lamar Graham (1995). "A Love Map to His Body". Redbook (May): 88.

- ^ Jyoti Puri 2002, pp. 604, 606–608.

- ^ Jyoti Puri 2002, pp. 633–634.

- ^ Wendy Doniger (2016). Redeeming the Kamasutra. Oxford University Press. p. sixteen. ISBN978-0-19-049928-0. Archived from the original on 21 Dec 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

General bibliography

- Apte, Vaman Shivram (1965). The Applied Sanskrit Dictionary (fourth revised & enlarged ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN81-208-0567-4.

- Avari, Burjor (2007). India: The Ancient Past. London: Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-35616-ix.

- Daniélou, Alain (1993). The Complete Kama Sutra: The Kickoff Entire Modern Translation of the Archetype Indian Text . Inner Traditions. ISBN0-89281-525-six.

- Wendy Doniger; Sudhir Kakar (2002). Kamasutra. Oxford World'south Classics. Oxford Academy Press. ISBN0-19-283982-9.

- Haksar, A.N.D; Favre, Malika (2011). Kama Sutra. Penguin. ISBN978-i-101-65107-0.

- Inundation, Gavin (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism . Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing. ISBN0-521-43878-0.

- Flood, Gavin, ed. (2003). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. ISBN1-4051-3251-5.

- Hopkins, Thomas J. (1971). The Hindu Religious Tradition. Cambridge: Dickenson Publishing Visitor, Inc.

- Keay, John (2000). Republic of india: A History. New York: Grove Press. ISBN0-8021-3797-0.

- McConnachie, James (2007). The Book of Love: In Search of the Kamasutra. London: Atlantic Books. ISBN978-1-84354-373-2.

- Jyoti Puri (2002). "Concerning "Kamasutras": Challenging Narratives of History and Sexuality". Signs. University of Chicago Press. 27 (3). JSTOR 3175887.

- Sinha, Indra (1999). The Cybergypsies. New York: Viking. ISBN0-600-34158-v.

External links

Original and translations

- Sir Richard Burton's English translation Archived 19 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine on Indohistory.com

-

The Kama Sutra public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Kama Sutra public domain audiobook at LibriVox - The Kama Sutra in the original Sanskrit provided by the TITUS project

- Kama Sutra at Project Gutenberg

jonesgribetwouter.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kama_Sutra

0 Response to "What Art Style Is Depicted in the Kama Sutra"

Post a Comment